To start at the end, with dramatic license.

“Glenn Woodsworth wants to meet you”.

“Oh, delighted. I would be delighted”.

“His accomplishments make what we've done look like child's play.”

So when we landed I left Simon to chat with this icon of old school Coast Range climbing. The disheveled PhD chic dirty-white-cotton clad bonhomme at the landing pad, a legend? Only judging from the tone of respect in Simon's voice, cause Simon is nothing if not a Coast Range legend.

How had I never heard of Glenn? How was my history knowledge so incomplete? Our traverse of the complete north-south Waddington ridgeline child's play? What had he done that measured so large in comparison? Refreshed from a wash, and letting my elders and betters chat about their shared passion and experiences, I surreptitiously fired up my moreish pocket computer and consulted the search engine behemoth, for I just barely fit into that generation that believes if it isn't on the internet it hasn't happened, unlike history, which has, happened.

Oh, U-Wall. And Pipeline. His identity popped out at me from the www.

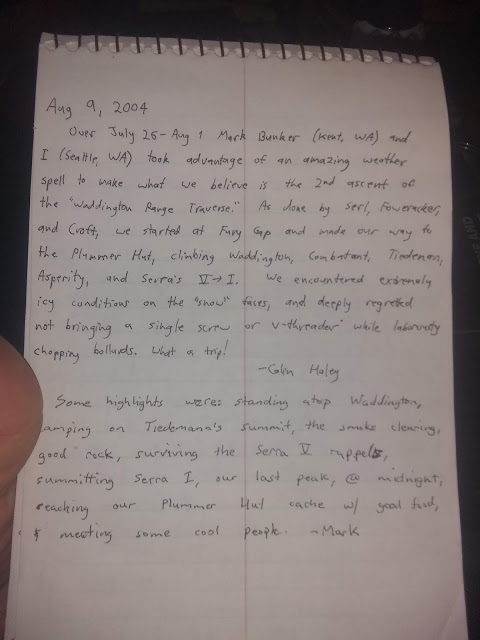

Simon had mentioned a note on an airdrop he had come across in his wide wanderings. “If we aren't back in two weeks we have headed north from this point”; to paraphrase. It was the closest thing to communication and rescue that Dick Culbert and Glenn had on one of their trips. “1964 saw Dick Culbert and Glenn Woodsworth dedicate five weeks to the Range that summer, knocking off a dozen first ascents (including Serra Five), and barely setting foot where anyone had been before.” (The Waddington Guide, Don Serl, p. 59.

Five days or five weeks. Times have changed. I couldn't even be bothered to ask the man himself or join the conversation, relying on digital media to form my impressions. I rushed over just in time to meet the man.

“You live in Golden? Then you know Bruce Fairley?”

“Barely. I'm not in town much.”

“Come on Glenn, we've gotta go.”

So it was I barely met a living legend. Chances delayed are chances missed.

But I did spend five days with another legend of the Coast Range.

Simon says he doesn't like to fail. Which is fine because he doesn't, at least not in the 8 trips he has done in the Coast Range, during which he has climbed a major new route on every trip. We "cheat" though, cause we fly in to the start of our routes (Culbert and Woodsworth flew in in 1964 too...), and tap the InReach when we want a pickup at the end of our five day journey. And we cheat with a little insurance, cached bags of food and fuel at the start (Fury Gap) and the end (Rainy Knob) of the trip. Still, Simon thought we didn't have much stuff for a Waddington traverse.

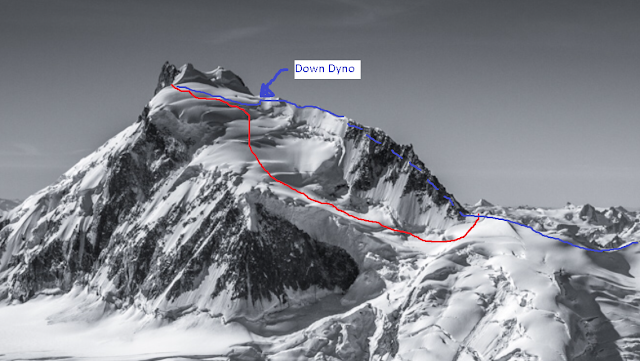

Simon's plan (he is the man with the plan) was to traverse Waddington via some new ground, from north to south. Another brilliant plan hatched like our last new route from a John Scurlock photo.

Simon has an eye for a line.

Red- Dias Glacier/ Angel Glacier route

We thought about bringing snowshoes, but on touching down on Rainy Knob to drop our end cache there was no blowing snow. We figured the week long storm we had delayed our trip for hadn't materialized in the mountains. Or maybe it had just been blown by the "river aloft" onto the north-east slopes.

Ohhh, this isn't going to take four hours. Not going to repeat Colin's effort...

We weren't going to beat Colin's time, we weren't going to walk about for a month, but it did seem we had our work cut out for us.

By 3 pm Simon suggested we stop for the day. "I am not in the habit of stopping at 3 pm when there is good weather in the mountains." "We aren't going to climb the ramp tomorrow, so why not let it clean off another day, and this is a perfect campspot." The voice of experience.

But the Wadd still seemed a long way off.

The spot was wonderfully flat, a perfect spot to camp. Important, as Simon doesn't believe in bringing unnecessary weight. The rad Rab two person tent is evidence, and if not pitched perfectly flat can seem a little "close".

On the second day we did much the same as on the first, climbing over peaks named artfully by the Mundays; Fireworks, Herald, Men-At-Arms, Bodyguard, Councillor. I was just silently glad we hadn't undertaken Simon's grand plan of the much longer link-up with the distant Mount Bell, above the appropriately named Remote Glacier.

Bell is in the central distant background in the photo above. When I mentioned to my well informed buddy Paul McSorley that we were flying in to the Remote Glacier he thought I was obscuring our goal. In fact, the usually uber-casual Paul had a tinge of worry in his voice when I mentioned that I was going to Wadd at all with Simon, for it is like bringing in the pinch hitter when you are playing away. The Bell/ Remote Glacier/Wadd linkup was thwarted by an unusually rainy June and July, but that is the type of line Simon sees in his mind.

By the second day we were camped at 2 o'clock, ready for an alpine start for the upper section of our ridge. Positioned across from the Skywalk buttress on Mount Combatant, I was beginning to feel like we were getting level with the big walls across the way.

I proposed afterward that we call the ridge "Tower Ridge" after the classic line on the Ben (Simon being the guidebook author). See why?

The next morning we were greeted by one of the magical moments that make such outings so memorable.

The tower ridge above, "the spine-like upper continuation of the ridge" (Serl, p.239), was going to provide us with a break from breaking trail. It's always fun going where nobody has been before. The climbing up the snow ramp on the south side of the ridge made a welcome break from the glacier walking.

There was no denying that three days of gaining elevation was starting to have an effect.

Before things heated up in the incredible continued high pressure, Simon was cresting the ridge as I passed onto the seemingly untrodden Epaulette Glacier.

Unprotected snow climbing is my least favourite kind. As we traversed through the top-out of Eamonn Walsh's Uber-Groove, we encountered just that. Surfing the very top of the snow ridge for a rope length, Simon belayed off a snow bollard using a somewhat old-school belay technique, telling me, "If you fall, fall to the left". As I was pirouetting on the cornice in an effort to au-cheval, I had to somewhat briskly ask which left. With no snow stakes present, we opted for a very powdery traverse of a 50 degree face. "It reminds me of the Cowboy Traverse on the Cassin. We just agreed that we would go as far as seemed reasonable before an avalanche would really cause you problems." With 4 screws total the math wasn't in our favor.

Simon isn't nearly as off-put by risk as I am after two years of guides' training. I was drilling v-threads on the traverse to keep the distances reasonable. Simon, when he took over, clearly embraced the age-old British strategy (as I believe Leo Houlding once put it) of running it out.

Then something I have never experienced alpine climbing happened. I have never down-dynoed alpine climbing before. When I seconded the traverse, Simon called up, "You have to jump into the bergshrund." And so that was how we joined the upper Angel Glacier. I hear that dynoing is all the rage in comp climbing, so logically it is the future as climbing moves into the Olympics. So, is down dynoing maybe the future of alpinism and Simon is just way ahead of the curve?

"Now you jump into the bergshrund"

The rest of the tale is more conventional. We summitted the North-West summit and the false summit, we camped out on another amazing flat spot at 3800m as our friends Paul and Tony hooted at us from the col, and the next day we climbed the highly enjoyable summit tower on Scottish style ice and solid cracks.

Little tent below.

I generally try not to look down on people, especially my friends, but I have to say it was a trip looking down on the inlets, the interior plateau, and our friends who were crack climbing across the way on Combatant that day, in one of the great alpine granite meccas of the world.

I couldn't possibly think of looking down on Tony though, cause at that moment I could look out and see the far off valley to the east that is home to Mike King and Whitesaddle Air, who had flown us in. It is also home to the Fosters ranch, from which Tony and Jason set out under their own steam to walk in, cross Fury Gap, make a strong attempt on a new route on Waddington, and then traverse far down the glaciers to the inlets I could see stretching off to the west, and the Pacific. Not to mention Paul's new route on the south side of Waddington. Respect to the pioneers come and gone, and to the youth who have the energy and the time and vision to undertake these great adventures.

And respect to Simon Richardson, the man with the plan and the Scottish climbing technique to boot. The Scottish belay technique I'm still not convinced about, but neither is he convinced about my claim that if we had tripped on the way down the upper Bravo Glacier we would have been visiting our friends sooner that expected.

Thus it is with adventure. Our friends become our friends by spending time together and trusting each other, and respecting our differences but sharing common goals. The genuine experience of common thrill-seeking courses through us. Something we recognize in each other, and keeps us striving on.

So, if you are interested in our adventure or conditions or going in there, why not get in touch. Or better yet, get in touch with Simon, cause he is the man with the plan. And we could chat, like I should have with Glenn, and we might become friends.